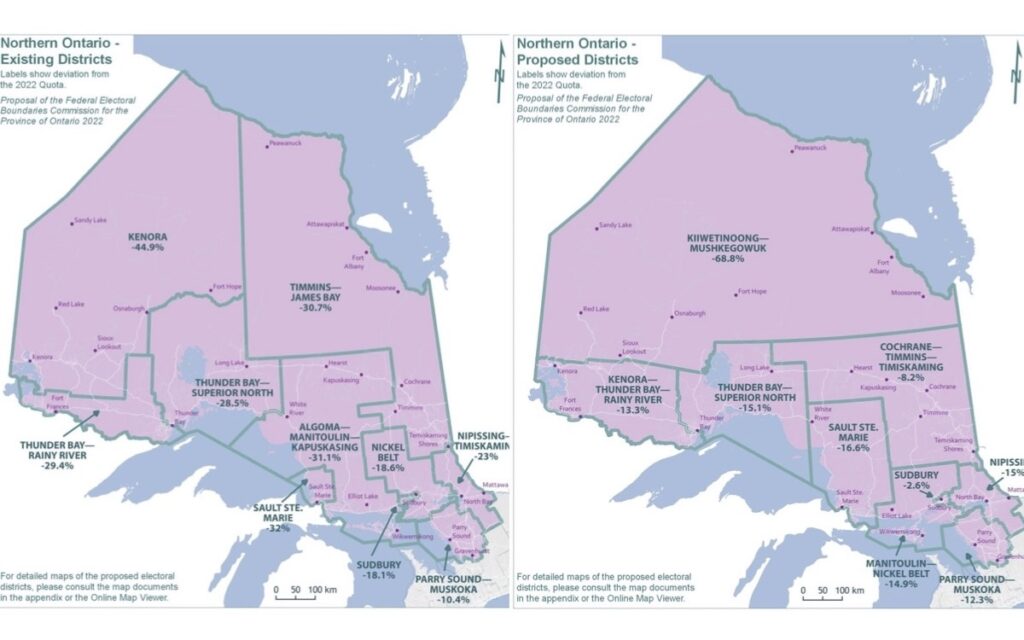

The Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for Ontario recently put forward a new electoral map for consideration. While the commission, broadly speaking, did a good job working through and within the legislative constraints and secondary concerns of the redistribution process, the proposed realignment does a disservice to constituents in Ontario’s far north, many of whom are Indigenous. Pictured are the existing ridings in Northern Ontario (left) versus the proposed ridings (right).

With the countdown on for the long weekend, Labour Day will mark the unofficial end of summer. Meaning that the dog days of summer are almost over, and life will start picking up again. That is no different in Ottawa than it is across Canada.

The rumour mill is in full speed as a potential cabinet shuffle is in the works ahead of next week’s federal government retreat. It is a real guessing game of who could be on the chopping block and who is next in line for a promotion. No matter what, the government could look very different as the Liberals prepare to play defence against a newly elected Conservative Leader.

Beside speculation on cabinet, parliamentarians’ futures are also at stake with the recently released riding redistribution, which sees a number of electoral districts chopped up and rejigged. A tangible change that could have a real impact on a politician’s ability to be re-elected and keep their six-figure job.

You may understandably wonder how objective MPs can be while talking about riding divisions. Unlike in the U.S., elected officials are not ultimately in control of choosing electoral boundaries in Canada.

Canada’s chief electoral officer is responsible for applying a legislated formula to decide how many members each province receives. From there, each province is assigned a commission to review the formula and adjust the provinces’ electoral boundaries accordingly. Each province has a three-person commission: a judge appointed by the Chief Justice of the province and two other members appointed by the Speaker of the House of Commons.

The Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, provides certain conditions to ensure that the number of voters in each riding is within a certain range, based on the provincial average. They also can draw boundaries to account for communities of “interest” or “identity” and historical divisions, or to ensure “manageable geographic size.” They can make exceptions for what the law calls “extraordinary” circumstances.

Unlike other provinces, Ontario’s commission only has to add a single seat.

To the credit of the commission, they have done broadly well. The proposed new ridings reflect how people in Ontario have adapted. The pandemic forced individuals to re-evaluate their lives, including how and where they worked. With offices being closed, there was no longer a need to be walking distance to the office or live right downtown.

People began to move out of the over-priced and often spaceless apartments, to houses in the suburbs or even the countryside. This has resulted in the city of Toronto losing an electoral district, but other regions, such as central Ontario, the eastern Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and northern GTA gaining a riding.

Though the commission has significantly let down those who live in Northern Ontario, a population that has never felt on par with the rest of the province. Instead of adjusting boundary lines, the commission decided to wipe out the two largest ridings in the far north – Kenora and Timmins-James Bay – and create a massive riding called Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk. It would span Ontario’s far north from the Manitoba border to Quebec.

Not only does this sound like an awful commute to work, as driving from one end of the riding to the other is literally impossible due to the lack of roadways, for the elected MP it is also unrealistic to expect them to represent such a diverse riding. The issues that matter to those in Moosonee are different from those in Red Lake or the challenges that those who live on the land of the Attawapiskat First Nation peoples.

These proposed changes are a true disservice to those living in Northern Ontario not only at the federal level but also provincially. As the federal government confirms their ridings, Ontario will be taking similar steps in the coming years and often is the tradition that the provinces mirror the federal ridings.

Ahead of the 2018 provincial election, the provincial commissions reviewed the ridings and agreed to make an exception and added an extra electoral district in the far north corner called Kiiwetinoong. The riding is 68 per cent Indigenous, the only riding in Ontario with a majority Indigenous population, and the riding’s name means “North” in Ojibwe.

This riding created a unique voice for Indigenous peoples, who are often underrepresented in politics, and solved the problem of a riding that is geographically oversized. Not to mention is a foot in the right direction to further aid in reconciliation and better support for Indigenous populations.

Like anything in life, nothing is perfect and there are a few changes needed before the ridings should be finalized. The first step is to ensure that those in Northern Ontario and Indigenous peoples are fairly represented. Without taking needed steps, the North could be shutout in the cold for decades to come.

Daniel Perry is a consultant with Summa Strategies Canada, one of the country’s leading public affairs firms. During the most recent federal election, he was a regular panelist on CBC’s Power and Politics and CTV Morning Ottawa.

Daniel Perry is the Director of Federal Affairs at the Council of Canadian Innovators, leading national advocacy and engagement efforts. With experience in consulting and roles at the Senate of Canada, Queen’s Park, and the Canadian Criminal Justice Association, Daniel has helped political leaders and clients across various sectors achieve their public policy goals. A frequent media contributor and seasoned campaigner, Daniel holds a Master of Political Management from Carleton University.