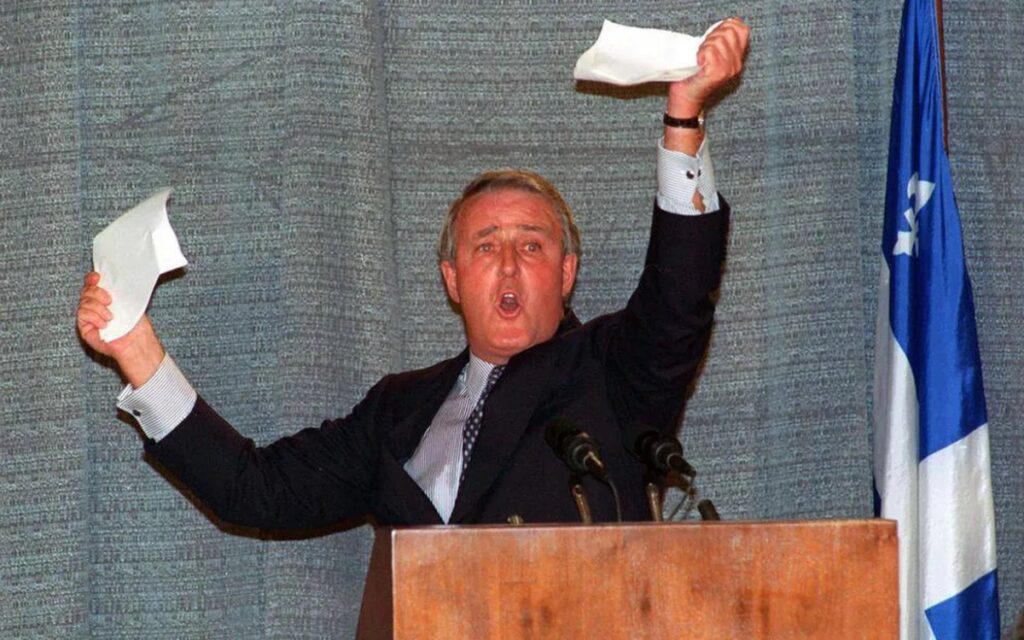

Exactly 30 years ago last week, Canadians rejected Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s 1992 attempt to add Quebec’s consent to the Constitution. Pictured Mulroney displays a piece of paper he had torn during a speech in Sherbrooke, Quebec in September 1992. The Prime Minister was demonstrating that a ‘No’ vote in the public referendum would rip apart the 31 items Quebec gained in the Charlottetown Accord. This column is the first in a two-part series. Photo credit: The Canadian Press/Fred Chartrand

The most recent example of Canada’s evolving constitutional development found new fodder with the Special Joint Committee on the Declaration of Emergency. As the Committee reviews the implementation of the Emergency Act this past February, Canadians once again find themselves grappling with the fallout of the Constitutional discussions held a generation ago, which culminated in the Charlottetown Accord referendum held on October 26, 1992, a full 30 years ago last week.

For the better part of five years, from 1987 until 1992, the Canadian people endured a lengthy wrangling over the recently patriated Constitution. After Pierre Trudeau, considered by many to be the architect of the 1981 constitutional deal, left office, his successor, John Turner, suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of Progressive Conservative leader Brian Mulroney. Mulroney had other priorities, but as his first mandate began to close, he felt burdened to address what he considered an egregious constitutional shortcoming, the exclusion of Quebec from the 1981 signing. Determined to right this wrong, our 18th Prime Minister undertook the unenviable task of reconciling Canada’s new constitutional framework with Quebec.

When Prime Minister Trudeau and the other premiers agreed on wording in the Constitution in 1981, Quebec had tried to negotiate a departure from Canadian Confederation a little over a year earlier. Under Premier Rene Levesque’s leadership, Quebec would not approve nor agree to any effort Trudeau made to bring Quebec into the new constitutional configuration. It left Canada incomplete in Mulroney’s mind, and after a few years, a new Liberal government in Quebec, and the passing of Levesque, it seemed right to begin to heal this division. Mulroney’s career as a labour lawyer, his devotion to a generous and united Canada, and his own political ambition served as further motivation.

The 1987 Meech Lake Accord attempted to complete Trudeau’s unfinished work. Meech secured the signature of all ten premiers, but there were deadlines to meet, new governments to convince, and Mulroney’s own battle for re-election, not about Meech, but on Free Trade. As the premiers gathered in Ottawa in June 1990, I recall being in a local hotel with a group of students visiting as part of a school trip. As we watched television in the evening, the reality that the unfolding historical talks convened just minutes away tempted both me and a parent chauffeur to head to Parliament Hill, determined to witness or be in the vicinity of what would certainly be considered momentous events in the years to follow.

Even the casual observer knew these matters held import. The arguments going back and forth were weighty and remained complicated as they did almost a decade earlier. Mulroney’s efforts to bring the partners into agreement, like Trudeau’s, required skill that only a master negotiator could accomplish. Bringing together the disparate interests of the vested Canadian provinces had eluded Trudeau. Mulroney had no illusions, but he entered the fray optimistically and with his usual high hopes.

Trudeau had forged ahead without Quebec’s signature. Mulroney did not have that option. The team of premiers Trudeau had included William Davis of Ontario and Peter Lougheed of Alberta, two giants worthy of the title, founding fathers. Davis’s generous compromises on behalf of Ontario and Lougheed’s exhaustive protection of Alberta’s natural resources set the tone and defined the interests of the provincial partners.

As Brian Bird wrote in The Hub, marking the 40th anniversary of the Patriation ceremonies, “Perceiving the federal-provincial impasse to be permanent, Trudeau announced in October that he would, without the consent of the provinces, ask the United Kingdom to patriate the Constitution with an amending formula and a bill of rights.” He ran into obstacles when eight Conservative premiers brought cases against the federal government’s ability to act unilaterally.

In November 1981 Trudeau called the premiers together one more time to hammer out an agreement. After days of discussion, Davis finally convinced Trudeau to accept a compromise which allowed for a “notwithstanding clause.” Unfortunately, Levesque had chosen to stay at a hotel in nearby Hull, Quebec, rather than stay at the Chateau Laurier in downtown Ottawa with the others. When he joined his colleagues the next morning he felt betrayed, refused to join the other nine who signed the deal, left in a huff, calling the event, “The Night of the Long Knives.” The Patriation ceremonies went forward, a reluctant Queen Elizabeth signing the document. Canada’s constitutional future looked uncertain and unsettled. Trudeau left office in 1984, Mulroney taking over a few months later after an unprecedented massive electoral victory.

Mulroney, in his infamous phrase, “rolled the dice” to resolve the problem of Quebec’s exclusion. Canadians, weary of constitutional wrangling, skeptically understood Mulroney’s interest in dealing with the matter. To their discredit, the First Ministers largely met in secret locking out the press. Their proposed 1987 deal, based on the five conditions the new Quebec government under the leadership of Robert Bourassa, led to the idea of a Distinct Society which proved to create further tussles in the years ahead. On April 30, 1987, all ten premiers signed the Accord, but the agreement needed to be ratified in all provincial legislatures and Federal Parliament within three years.

During the interceding years Mulroney won a new mandate in 1988, mentioning little about Meech. Meanwhile, several provincial governments changed hands and many of them opposed the originally popular accord. As the ratification date neared, Mulroney assigned the duties of Constitutional Affairs Minister to former Prime Minister Joe Clark, charging him with the task of breaking the logjam. The premiers and representatives gathered in Ottawa knowing that Newfoundland’s new premier, Clyde Wells, had rescinded the province’s previous support, while Manitoba required unanimous consent to satisfy procedural changes before its legislature could vote to approve.

Facing these challenges, the First Ministers could not resolve the objections of Wells, who “argued that Meech Lake would give Quebec greater legislative powers than the other provinces, make it almost impossible to enact future constitutional reforms, and undermine federal funding to Canada’s poorer provinces.” He also protested because, “No federation is likely to survive for very long if one of its supposedly equal provinces has a legislative jurisdiction in excess of that of the other provinces”. In the case of Manitoba, an obscure member of the legislative body, Elijah Harper, spoke for a diversity of groups who believed their interests had not been represented nor heard. His unwillingness to grant unanimous consent blocked Manitoba’s legislature from proceeding to approve. Later, New Brunswick also withdrew its previous support for the agreement. And, it should be noted, former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau voiced his grave concerns regarding Mulroney’s efforts, further eroding support and complicating its passage.

In the second part of this column, I will chronicle a deeper dig into the fascinating Trudeau-Mulroney dynamic, the eventual 1992 referendum outcome, and its implications for Canada today and into the future.

Dave is a retired elementary resource teacher who now works part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, where he earned a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who now works part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, where he earned a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.